After having so much fun with the stables last month in celebration of the Survivor Series, we’ve decided to turn this December — and all Decembers in perpetuity — into Promotions Month. For a curtain jerker, we have WCW and its predecessor, Jim Crockett Promotions. This is Day Two of #JCPWCWWeek, the fourteenth installment of our (patent-pending) Juice Make Sugar Wrestler of the Week Series. We mixed it up by making JCP and WCW a Promotion You (Should) Probably Know Better in two parts. Yesterday, we talked about the transition from JCP to WCW, and today we’re giving you the finer points of JCP’s oeuvre with some Essential Viewing then finishing the epic story of the great lost promotion of our time. On Wednesday, we’ll expose some harsh truths with the debut of Lies The WWE Told Us. After Hump Day — and throughout the week — we’ll be quenching your thirst for Listicles with a Juice Make Sugar Top 10 List and a couple of odds, before ending everything with a Difference of Opinion, where JMS HQ erupts in a civil war, which will take place inside of a Doomsday Cage.

It’s fundamentally impossible to provide an Essential Viewing of pre-80s Jim Crockett Promotions: there isn’t a lot of decent-quality surviving tape out there because it was over thirty years ago, and (as fans of Dr. Who know) it wasn’t uncommon practice as a cost-cutting measure to tape over old shows in the days of syndication and even if the video had survived, to internet generation types who post videos of wrestling online, anything before the computer revolution might as well be a blurry daguerreotype of a Civil War soldier’s ass.

And so, in spite of thirty years of prior history, we’ll touch on the biggest (and last) decade of JCP’s existence: the 1980s, before Nick provides undeniable video evidence that they took all of the greatness they had in North Carolina, moved to Atlanta, became WCW and crapped all over it.

In the 1970s, Wahoo had been a huge part of the Mid-Atlantic’s transition from featuring mostly tag teams (as I covered yesterday) to being a territory with legitimate main event singles matches. McDaniel legitimized first the Mid-Atlantic Heavyweight Championship through his feuds with Johnny and Greg Valentine and then later the United States Title when it became JCP’s top singles title (not counting the traveling NWA’s World’s Champion.)

So when he took on Flair — who for anyone that managed to watch wrestling outside of the WWF’s considerable shadow was the 1980s in professional wrestling — it was undeniably fascinating, even if only to see the spectacle of the territory’s top star of ’75-’80 wrestling the top star of ’80-’88.

The fact that Flair and Wahoo held the World and U.S. title belts respectively places this match in the fall of ’81 during Flair’s first run as “The Man.” and while the match isn’t either man’s best, as Wahoo was past his prime at this point, Flair was a fantastic athlete at the time (as he was for much of his career) and coming into his own as a character. Furthermore, it’s interesting to see the tricks that Flair took from Wahoo and made his own: the way he paces the match early, the stiff chops to pop the crowd, the well-timed color, among others.

As the 80s took shape, Ric Flair’s talent and charisma were so evident that the Crocketts would have been fools not to hitch their wagon to him. Pushing Flair became the top priority of JCP (and by extension the NWA who they largely steered) to the point that the first Starrcade was literally called Starrcade ’83: A Flair For The Gold (which should have carried the subtitle: Spoiler Alert, He Wins).

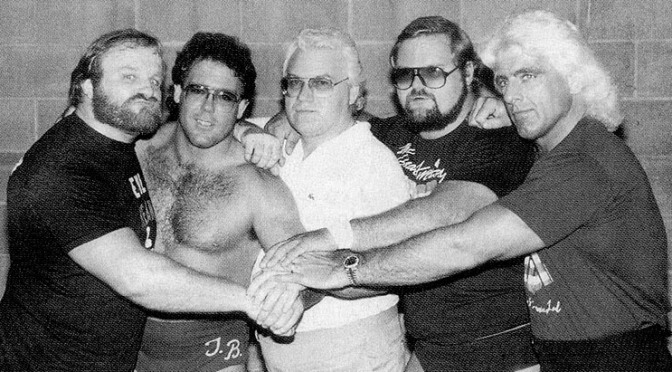

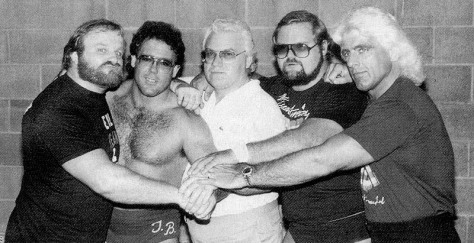

In the build to Starrcade, the Crocketts cast Flair as the hometown boy about to make good by taking on big bad Midwesterner Harley Race. Flair wasn’t as magnificent a babyface as he was a heel, but he knew what to say and do and how to play to the fans in the Mid-Atlantic. This set of promos from the build-up to Starrcade shows Flair cutting promos on Race and pledging assistance and brotherhood to babyface (and once and future rival) Ricky Steamboat.

As we touched on last week with our Tully Blanchard feature, Jim Crockett Promotions at its height wasn’t just about Flair and Dusty, it was about robust cards filled from top to bottom with some of the greatest role players of all time. The mid-to-late 80s were a deep era for tag team wrestling in both the NWA and the WWF, and one of the Crocketts’ most valuable acts at the time was The Rock ‘n’ Roll Express.

Neither Ricky Morton nor Robert Gibson was a total package as a wrestler, but as a team they were one of the top ten acts of the 1980s. Even on worn out old tapes, their matches sound like Beatles concerts with near-constant high-pitched feminine screams throughout. Ricky Morton got the heat on heels with his selling as well as anybody every did, and Robert Gibson cleaned house in a way few wrestlers of his size ever could. If men (or in this case tag teams) are to be measured by the mark the make on history, The Rock ‘n’ Roll Express are one of the most important tag teams of all time. Easily half of the babyface tag teams that followed them from The Rockers to The Hardy Boyz were direct imitations of the The Express.

This match sees The Rock ‘n’ Roll Express take on NWA Tag Team Champions Ivan Koloff & Krusher Krueschev (two evil Soviets played by a Canadian and a guy from Minnesota). The match is ‘80s tag team psychology at its best and helps illustrate how good both wrestlers and promoters were at giving the fans what they wanted to see at this point.

As our journey finds us in 1985, it would be impossible to write anything about Jim Crockett Promotions resembling Essential Viewing without talking about Hard Times. As we covered last week, The Four Horsemen broke Dusty Rhodes’ ankle in maybe the biggest injury angle of all time. When Dusty came back, he cut the now-legendary Hard Times promo, connecting his own suffering as a wrestler to that of working class Americans whose industrial jobs were suffering in the early days of Reaganomics. Hard Times is to wrestling as Born in the U.S.A. is to rock music. Was it presumptuous for the rich and famous Rhodes to compare himself to struggling laborers? Probably. Did it get him white hot over? You know it!

In the latter half of the 80s, Jim Crockett Promotions’ goal was to wrap up the pantheon-level Dusty-Horsemen feud in a way that created the next big star to lead the NWA. The Crocketts and booker Dusty Rhodes were heavily invested in pushing Terry Allen, known as Magnum T.A. (Tom Selleck pun? Yeah, we’re in the 80s.) as the next top babyface in the territory. Allen brought a lot to the table: he had a good look, could talk so well he often did color commentary, and understood how to build sympathy and build a comeback.

Dusty rubbed Magnum T.A. the only way he knew how: by putting him storylines with the great Dusty Rhodes. Rhodes’ self-centeredness aside, the plan worked, and following a fantastic feud with Tully Blanchard (some things just keep coming up, don’t they?) that culminated in their brutal, amazing I Quit cage match at Starrcade ’85, Terry Allen looked well on his way to becoming the next face of Jim Crockett Promotions.

This match shows Magnum at the height of his babyface powers taking on Nikita Koloff. Nikita was not a great worker, but he had tons of Cold War heat and played his character well. This match displays everything that was right with Terry Allen. If you close your eyes and imagine an alternate course of history, you can see how the guy who wrestled this match could have gone on to do big things.

Unfortunately for JCP, wrestling fans, and most of all, Terry Allen himself, Allen was involved in a horrific car wreck in the fall of ’86 that left him paralyzed and ended his career. In addition to being a tragedy on a human level, Allen’s accident was a kick between the legs to JCP and the NWA, who were close to putting their eggs in his basket.

In an interesting turn of events, with Magnum T.A. unable to wrestle, Dusty and the Crocketts decided to turn his rival Nikita Koloff babyface. In a move that shook the foundations of Cold War wrestling booking, Koloff showed sympathy for his injured opponent and essentially claimed to fight in his honor in spite of their political differences.

Two years later, Jim Crockett Promotions would be out of gas and out of money. The loss of Magnum T.A., the cost of jet fuel, and the company’s decision to serve two masters by promoting nationally while still trying to stay a regional company all came together into a thick, meaty stew of failure. The Crocketts, The Horsemen, and Dusty Rhodes had created some of the greatest wrestling moments of all time during the ‘80s, but they had been crushed by the weight of their own ambitions. Even though Ted Turner acquired JCP’s roster, title belts, and lineage, something died when the last great regional promotion became a cable TV show.

***

After making it through much of the pre-nWo fiascoes following the transition of the organization from the wrestling offshoot of a promotions company to the wrestling offshoot of a media company.

Even though it marked a paradigm shift as massive as anything the industry had seen before, Hulk Hogan turn into “Hollywood” Hogan at 1996’s Bash at the Beach wasn’t even the most remarkable thing that happened that night, nor would it have the longest-lasting impact on the industry. That distinction belong to the first match of the night, a lucha libre barnburner between Psicosis and Rey Mysterio, Jr:

The bout, which ends after a top-rope powerbomb from Psicosis being reversed into a hurricanrana by Mysterio, gives a delicious slice of the true lesson/legacy of WCW, and its predecessor, Jim Crockett Promotions, the idea that being a global phenomenon in the world of professional wrestling means doing everything, and doing it well. A card from the golden era of post-NWA WCW — essentially between the ‘96 Great American Bash, from just one month before this match to July 6, 1998, when Goldberg defeated Hulk Hogan on an episode of Nitro (for free) — is like remind you of what most of the cards for WWE PPVs look like today, with an eclectic mix of performers, gimmicks and story lines that scream “there’s something here for everyone, we promise!”.

But, as we talked about yesterday, this was the Terry Bollea show. Instead of allowing the things that needed to happen to build a company around the wattage and heat that came from the nWo’s name on the marquee, Bollea — along with Nash, Hall and eventually Vince Russo — would do seemingly whatever it took to keep their names in lights.

The nuts and bolts story of WCW’s downfall is well-tread, even by yours truly. There are pressures points that are brought up constantly: ending Goldberg’s streak with a cattle prod, the Fingerpoke of Doom, Ric Flair being declared insane and ending up at a mental institution, the Russo-Hogan incident, Ed Ferrara’s raison d’etre:

Which makes sense, as these moments, and the moments like them are “what” caused WCW to fail. The “why”, comes from a much different place, though. Someone in charge thought most of these were a good idea, whether it was for the company, for wrestling or for themselves. That’s the only explanation for letting people like Chris Jericho, William Regal, Eddy Guerrero, Dean Malenko, HE WHO SHALL NOT BE NAMED and Brian Pillman go, even after matches like these:

Unlike JCP, who was put out of business WWF largely through backroom political/business maneuvering and machinations, WCW’s “lost” the battle against Vince McMahon much more than he won it. And because of this, WCW’s demise meant something much larger. Ending the way it did didn’t just mean that the WWE had lost a competitor for cultural hegemony. It meant it had lost competition for cultural hegemony, period.

By proving unable to beat out WWE even with piles of Ted Turner’s money, it created a vacuum both inside the industry — by leaving almost the entirety of recorded wrestling in the hands of one entity — and wreaked havoc on any other high-profile media company — the only people who could possibly match WWE’s production values and marketing muscle — ever trying to reach for the throne again.

We’ll spend more time this week talking about what that all means, but ultimately, it means that professional wrestling is worse off for what happened to WCW, and because of that, we’re all worse off. Period.